Does the culture we are raised in influence what we remember about our favorite childhood food? Would the Dutch differ in this from Expats? And if so, how?

We discussed these questions with participants of our event in Amsterdam on ‘Taste, Memory & Culture’.

What is it that makes a certain type of food from our childhood so special to become unforgettable; is it the food itself, the situations surrounding it, or both? In those discussions, it was obvious that everybody was recalling very special and nostalgic moments. The participants were both Dutch natives as well as Expats living in Amsterdam.

The key term nostalgia, a ‘sentimental longing for the past’, always includes ourselves in a central position, whether it refers to family meetings, reunions, birthdays, or scenes from holidays. Nostalgia invariably prompts a wave of positive and warm emotions!

A traditional or a globalised dish?

When I asked ‘which is your favorite food from your childhood?’, a slight but clear smile appeared on all faces. Was the `favorite’ a traditional food from one’s ‘own culture’, or rather something ‘from abroad’. Would these memories be different for Expats than for the Dutch, and if so, in what sense?

After welcoming our participants with a drink, they were asked to write-down their answers on 3-4 food memory related questions, like ‘which is your favorite food from your childhood’ and ‘what is so special about this memory’.

Analysis of the answers after the event revealed cultural differences as well as universal trends. It was e.g. striking that as many as 68% of the Dutch, who by the way were between 19 to 26 years old, named a non-traditional type of food. For example, a French dish (boeuf bourguignon), an Italian (spaghetti Bolognese) one and even a Japanese one (sushi). The remaining 33% of the Dutch, from another generation now mostly in their 50ies, did recall a typical Dutch ‘delicacy’, like ‘boterham met pindakaas’, ‘boterham met spek’ or ‘draadjesvlees’.

But, it was remarkable that all Expats—mostly from Southern and Eastern Europe–, regardless age and without any exception, remembered something typically traditional. For an Italian it was ‘milk with biscuits’ before going to bed, for Greeks a ‘spinach pie’ (spanakopita), or spaghetti with minced meat (the Greek style) for a Dutch-Hungarian a comforting potato dish called ‘rakott krumpli’. Dishes were made either by a grandmother or mother herself.

Cultural or shared context?

We also analyzed the answers related to the situation in which the ‘unforgettable’ memory is placed. What matters here, is what comes ‘first in our mind’.

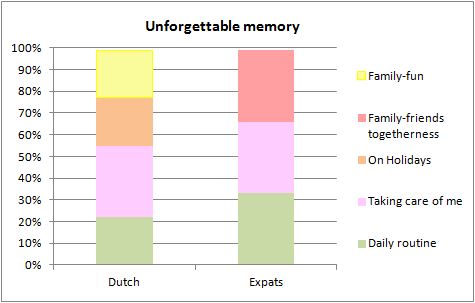

We all tend to memorize specifically that what makes us happy. The answers given by 22% of the Dutch and 33% of the Expats placed their ‘unforgettable’ memories in the context of their families. There was, however, a critical difference: Whereas, the ‘Dutch’ thoughts centered on ‘me’ having fun in making something creative within my core family (see the example of ‘sushi’ in ‘Family-fun’ subcategory), Expats recalled themselves in a self-extended diffused form. They talked about happy atmosphere within the wider family and many friends (see example ‘mussaka’ in ‘Family-friends-togetherness’ subcategory).

We should note that in both case one feels good; either because you feel proud of yourself for being innovative or creative, or because you are sharing your time with people you love and feel familiar with. One may argue that the one case does not exclude he other. True, but what in experimental psychology counts is what ‘comes first in our mind’! The elements our memory has encoded to remember reveal what for ‘me’ is important in life. Like in these two subcategories, it can be influenced by our cultural upbringing.

For example, if in culturally —mixed couples, mixed families, expats living in ‘another’ culture— one think of ‘me’ being creative and the other of the atmosphere of togetherness, is what can trigger ‘out of the clear blue sky’ frustration and even serious confrontations. as for all of us, ‘own’ background underlying input is less consciously realized.

Another 22% of the Dutch remembered discovering their ‘childhood favorite food’ while being ‘On holidays’ (e.g. in Italy). As the figure shows, the answers ‘On holidays’ and ‘Family-fun’ memories occurs only among the ‘Dutch’, while the ‘Family-friends-togetherness’ answers only among the Expats (See Figure).

Both Dutch and Expat participants commonly produced the ‘Routine’ type answer, when they bring to mind a daily habit, and also the ‘Taking care of me’ type. While for the Dutch (22%), routine mostly referred to ‘school’ and lunch-time (‘boterham met pindakaas’), for an Italian ‘before going to bed’ (‘milk with biscuits’), for a Greek, ‘after ‘school  and lunch-time (‘boterham met pindakaas’), for an Italian ‘before going to bed’ (‘milk with biscuits’), for a Greek, ‘after school’ (usually as lunch, ‘Moussaka’).

and lunch-time (‘boterham met pindakaas’), for an Italian ‘before going to bed’ (‘milk with biscuits’), for a Greek, ‘after school’ (usually as lunch, ‘Moussaka’).

Lastly, ‘Taking care of me’ is represented equally (33%) in each group. The trip down memory lane goes to the person who prepared the favorite dish, grandma (for the younger) or ‘ma’ (for the older). You see two characteristic descriptions of the latter type on the right.

We thus found both universal and culture-specific memories.

A message for food professionals?

Although this was only a small survey, which, however, did show clear trends, it does suggest directions for further investigation, especially for Dutch or Expats who run professional food business. Even if, as Heraclitus once said, ‘everything flows, nothing stands still’, it is essential to know the basics of what it is about being ‘at the table’ that makes people from the one or the other culture feel happy!

Nostalgia prompts anyway self-positiveness

Psychologically speaking nostalgia is ‘a reservoir of positive affect’. Is it our creativeness from childhood, nice summers or holidays, childhood visits to grandma or the figure of our ‘ma’ that makes it unforgettable? Whatever it is, it boosts a positive sense of self-continuity for all of us!

Do the differences support previous findings that the Dutch are more open, more innovative and love changes more compared to other cultures?

Do Expats from certain cultures love their ‘own’ traditions more strongly or do they have a stronger need for maintaining cultural identity and ‘belonging’ compared to the Dutch? Is it a product of the loneliness Expats often experience, a realization of the importance of a beloved person ‘back home’, a need to connect their origins with their host society?

Whatever it is, nostalgia enhances our being! Moreover, as research has shown, nostalgia can buffer the acculturative stressors immigrants experience as they strive to adjust to their new culture.

Scientific Literature

Oyserman, Daphna, and Spike WS Lee. “Does culture influence what and how we think? Effects of priming individualism and collectivism.”Psychological bulletin 134.2 (2008).

Sedikides, Constantine, Tim Wildschut, and Denise Baden. “Conceptual Issues and Existential Functions.” Handbook of experimental existential psychology (2004).

Sedikides, Constantine, et al. “Buffering acculturative stress and facilitating cultural adaptation: Nostalgia as a psychological resource.” (2009).

A similar version of this post has been published in I am Expat.nl too: